Introduction

One of the tricks to great writing is to make good use of literary devices. Literary devices are the techniques writers use to help them communicate their ideas more colorfully, more meaningfully, and most effectively. They often involve the use of figurative language and things like metaphors, similes, symbols, exaggeration, irony, assonance, and alliteration. All great writers use literary devices, whether in poetry, prose, essays, or commentaries. Just like a musician uses all the tricks of the trade to win the ear of the listener, writers must use all the tricks of their craft to win their reader. In this article, we’ll talk about literary devices and what they are, and we’ll give some examples, too, to help you learn how to use them.

What are Literary Devices / Definition

Literary devices are tools or literary techniques that help a writer unlock the potential of his words. Ever tapped a tree to get the maple syrup out? That’s what using literary devices is like (in fact, I’ve just used one here with this simile). It’s a way to get the meaning across without being bland, boring, dry, and dull. It adds sugar and spice, makes it tasty for the reader, keeps it interesting and zesty, and deepens the experience. You’re not likely to see many literary devices in purely technical writing; but in all other types—from speeches to essays to fiction—you will start to notice literary devices galore, once you know what to look for.

In short, a literary device is a way of adding color and depth to one’s writing. Techniques can range from figurative writing to putting two dissimilar things together (i.e., juxtapose ideas to bring out the sharp contrast). It is a type of language used to create more interesting and effective descriptions, to express ideas more fully without being complicated about it (i.e., expressing more completely but also more simply), and to make the language stand out, pop, seem more vivid and alive.

For example, one literary device that often goes unnoticed but is very helpful in creating sensory experiences for the reader is the use of gustatory imagery. This technique involves describing tastes so vividly that the reader can almost savor them. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is full of descriptions of magical feasts and treats, where the gustatory imagery makes you almost taste the pumpkin pasties and butterbeer. Indeed, pumpkin pasties are a particularly nice touch because it represents two devices: imagery and allusion. The allusion is found in the fact that pumpkins are associated with Halloween, and Halloween is a dress-up time for kids; Harry and his friends enjoy pumpkin pasties on the train to Hogwarts, and the association of going to Hogwarts with pumpkins makes it easier for young readers to enter into the world of make-believe, as their train-of-thought is already thinking “dress-up” due to the association of pumpkins with Halloween and costumes. It is a brilliant bit of writing on the part of Rowling.

View 120,000+ High Quality Essay Examples

Learn-by-example to improve your academic writing

Another example is in Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven,” where the poet uses all kinds of literary devices to bring the scene alive for the reader. Alliteration is rampant in the poem: one can see the repetition of sounds in lines like “And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain / Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before” and ‘Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.” These are just two examples of how sounds sweep the reader along. But there is also the image of the ominous bird itself, which is meant to evoke death and gloom—and the fact that it perches itself “upon a bust of Pallas,” itself a symbol of wisdom, is a great use of irony as the bird symbolizes irrational fear sitting in a position of dominance over a symbol of reason.

The great thing about literary devices is that they are used to communicate all of these ideas subtly so that the reader hardly even realizes what is happening, although everything is felt and experienced below the surface.

To get a sense of how important literary devices are, let’s compare an excerpt from Poe’s “The Raven” to an excerpt in which the same passage is rewritten but without literary devices.

| Original Excerpt from “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe (with Literary Devices):

“Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore— While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. ‘Tis some visitor,’ I muttered, ‘tapping at my chamber door— Only this and nothing more.'” |

Rewritten Excerpt without Literary Devices:

“It was a late night, and I was sitting, feeling tired and weak. I was looking at some old and unusual books. While I was almost asleep, I heard a sound, like someone knocking at the door of my room. I thought it must be a visitor knocking at my door, and that’s all it was.” |

The original verses with literary devices set a definite mood, a rhythm, a tone, an atmosphere, and a feeling of unease that simply cannot be matched in the excerpt where no literary devices are used.

In the rewritten lines, the richness and rhythm of Poe’s original text are all but absent. The original’s use of alliteration in “weak and weary,” the internal rhyme in “napping, tapping,” and the repetition in “rapping, rapping at my chamber door” contribute to the poem’s haunting undertones. The phrase “Once upon a midnight dreary” sets a dark, mysterious, ominous note, which is lost in the plain description of “It was a late night.” Plus, the original’s use of a first-person narrative creates a sense of immediacy and personal involvement, which is diminished in the more straightforward and detached rewrite.

Let’s look at another example, this time using an excerpt from William Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” (which uses literary devices) and then rewrite it without them:

| Original Excerpt (with Literary Devices):

“I wandered lonely as a cloud That floats on high o’er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host, of golden daffodils; Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.” |

Rewritten (without Literary Devices):

“I walked alone, Above valleys and hills, And then I saw many yellow flowers; They were next to the lake and under the trees, Moving in the wind.” |

In the original verses, Wordsworth uses several literary devices that enlarge the text. The simile “lonely as a cloud” establishes a big scene and or canvass, and conveys the speaker’s sense of solitude as well as the wide open space in which he travels. The personification of daffodils as “fluttering and dancing in the breeze” gives them to life and brings the overall setting a sense of joyfulness and serenity. The use of words like “crowd” and “host” for the daffodils is further use of personification, making it seem as though the narrator could commune with nature quite literally.

In the rewritten version, the absence of these devices results in a more straightforward and less evocative text. There is no nuance or subtlety to it, and much of the meaning has been removed as a result. The sense of wonder and the emotional resonance of the scene are diminished. The imagery is less vivid, and the overall poetic quality and rhythm of the original are gone. Thus, one can see that literary devices are integral to creating the beauty and depth of poetic expression.

G.K. Chesterton was another master of literary devices. His essays are brimming with them and, therefore, make a great example for how their usage can elevate one’s language and train-of-thought.

| Original Excerpt from “On Running After One’s Hat” (with Literary Devices):

“An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered. The hour of peril is the hour of splendour. The inconvenience of the rain is an adventure for the child who seeks the rainbow, but an ordeal for the adult who has forgotten the colours.” |

Rewritten Excerpt (without Literary Devices):

“An adventure is just a situation that you think about in a positive way. If you think about it negatively, it’s just a problem. Dangerous times can be exciting. Rain is fun for a child who is looking for something beautiful, but it’s a problem for an adult who doesn’t see it that way.” |

In Chesterton’s original text, his use of paradox (“An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered.”) immediately captures the reader’s attention and encourages them to see common experiences from a new perspective. There is also a sharp use of contrast used by Chesterton, as between the child and the adult in their reactions to rain; this contrast provides unspoken commentary on the loss of wonder and imagination that often accompanies adulthood. The phrase “the hour of splendour” is a grand way of expressing how moments of challenge can be wonderful when approached like with childlike innocence.

The rewritten text is stripped of these literary devices, and in becoming more straightforward it loses much of its charm and depth. The paradox is replaced with a simplistic explanation, and the contrasting frame of mind between the child’s and the adult’s perspectives is reduced to a basic comparison of experience. The nuanced encouragement to reframe one’s perspective on life’s inconveniences is lost as the literary devices are shelved, and the text acts as more of a direct, dull statement than a thought-provoking reflection.

Let’s do one final example, using George Washington’s Farewell Address.

| Original Excerpt from George Washington’s Farewell Address (with Literary Devices):

“The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so, for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that, from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness.” |

Rewritten Excerpt (without Literary Devices):

“Your government’s unity, which makes you a single people, is important to you. This is good because it is a key part of your true independence. It helps maintain calm at home, peace with other countries, your safety, your success, and the freedom you value so much. However, it’s clear that for various reasons and from different places, efforts will be made to make you doubt this. Both internal and external opponents will consistently target this aspect of your politics, often in hidden and tricky ways. Therefore, it is very important for you to understand how much your national unity contributes to your happiness, both as a group and individually.” |

George Washington’s original is filled with literary devices that support its rhetorical power. The metaphor of the government as a “main pillar in the edifice of your real independence” and other aspects of national well-being is particularly effective. It conveys the importance of unity and frames it as a foundational structure that is needed to maintain a prosperous nation. The use of parallelism in listing the benefits of unity (“your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize”) adds cadence and rhythm to his argument and helps him to emphasize these benefits.

The rewritten text maintains the core message, but it lacks vigor, imagination, metaphorical depth, and the rhetorical strength of the original. The metaphor of the government as a pillar and the parallel structure are replaced with duller but more direct statements, which result in a loss of the persuasive quality that Washington’s words carry. The original’s eloquent and structured presentation of ideas gives a grand sense of gravity and urgency that is simply missing in the plain rewriting.

How to Identify and Use Literary Devices in Writing

To identify literary devices, one must first become familiar with the different types of devices. Read widely across genres and look for patterns and usages of devices like metaphors, similes, personifications, and others. Pay close attention to how authors use language to convey emotions, create imagery, generate interest, make a point, embellish an argument, or emphasize ideas. Understand the context in which these devices are used – the setting, character emotions, the overarching themes – context is very important in understanding how and why literary devices are being used.

Using literary devices in writing requires a careful approach. The choice of device should align with the message or the idea or the emotion the writer intends to convey. For example, metaphors and similes are excellent for creating powerful descriptions that convey deeper meanings (implied by the image used). Irony can be used to convey subtle points or to present complex emotions in a simple way. Irony can also be used with satire to critique social norms or deviations.

Overall, it is important to use these devices sparingly and purposefully. Overusing literary devices or using them when it is not reasonable to do so can overwhelm the reader and make the writing superfluous.

Experimenting with different devices in various types of writing can help in understanding their effect. For example, in creative writing, you can try using symbolism to add depth, while in persuasive writing, you can try using analogies to make your arguments more convincing.

The key when using literary devices is to enhance your writing, not distract from it.

Literary Devices List

Main Literary Devices

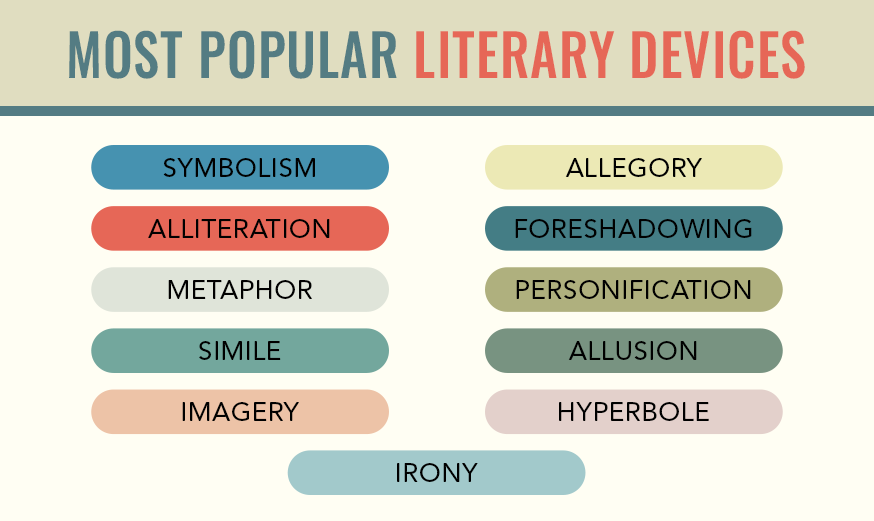

Some literary devices are used so frequently that you can find them readily across various genres. Here are some of the most popular literary devices in use today:

- Symbolism: This is the technique of using symbols to ascribe ideas and qualities to one thing by calling to mind the characteristics of another; i.e., giving an object representative meaning that is different from its literal sense. For example, a black cat may symbolize something ominous in a Poe story; a storm may symbolize moral disorder in a Shakespeare play.

- Alliteration: This technique involves the use of repetition by repeating the same consonant sounds at the beginning of words in close sequence. For example, “Fuzzy Wuzzy was a bear. Fuzzy Wuzzy had no hair. Fuzzy Wuzzy wasn’t very fuzzy, was he?”

- Assonance: This technique involves the use of repetition of vowel sounds. For example, “The early bird catches the worm,” where the ‘ea’ and ‘ir’ sounds are repeated.

- Metaphor: This is a figure of speech in which one thing is said to be another. For example, “The note was a killer.”

- Simile: This is a figure of speech in which one thing is said to be “like” another thing. For example, “Her smile was as bright as the 4000 watt light bulb.”

- Imagery: This consists of descriptive or figurative language used to create strong pictures that appeal to any or all of the five senses—such as visual imagery (sight), auditory imagery (sound), olfactory imagery (smell), gustatory imagery (taste), and tactile imagery (touch).

- Allegory: This is a simple story that contains a deeper, symbolic, or a hidden meaning, usually one with a moral purpose.

- Onomatopoeia: This is a word whose speech imitates the natural sounds of the thing it describes—like a phonetic sound effect that amplifies the description so as to make it more expressive and interesting. For example, “The bees buzzed and blitzed the intruder.”

- Irony: This technique draws contrast between what is stated and what is left unsaid, or between expectations and reality. This includes verbal irony (saying the opposite of what one means), situational irony (when the opposite of what is expected occurs), and dramatic irony (when the audience knows something the characters do not).

- Foreshadowing: This is a literary device used to suggest or hint at what will come later in the text.

- Personification: This is the practice of giving human characteristics to non-human things. For example: The wind howled; the moon sang.

- Allusion: This is a brief and usually indirect reference to a person, place, thing, or idea of some significance. It does not describe in detail the person or thing to which it refers, but the object is typically well-known.

- Hyperbole: These are exaggerated statements or claims used to make a point but not meant to be taken literally. For example, “I’ve told you a million times to cut that out!”

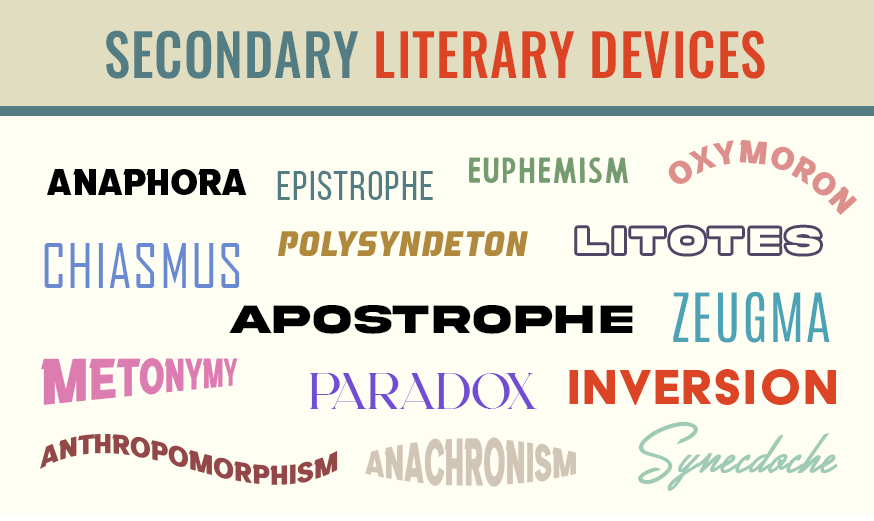

Secondary Literary Devices

Beyond the most commonly known literary devices, there are many others that writers use to improve their storytelling, strengthen their rhetoric, deepen the meaning of their ideas, or get their audiences more engaged. Here’s a list of additional literary devices, how they work and what they look like:

- Anaphora: The repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses or sentences. For example, Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous repetition of “I have a dream” in his speech. Or: “Every day, every night, in every way, I was falling further behind.”

- Epistrophe: The opposite of anaphora, this is the repetition of a word or phrase at the end of successive clauses. For example, “of the people, by the people, for the people” from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

- Euphemism: Using a mild or indirect word or expression to replace one considered too harsh or blunt when referring to something unpleasant or embarrassing. For example, saying “passed away” instead of “died.” Or: Referring to someone being “let go” from their job instead of “fired.”

- Oxymoron: A figure of speech in which contradictory terms appear in conjunction. Examples include “jumbo shrimp” and “deafening silence.”

- Asyndeton: The omission of conjunctions between parts of a sentence, used to shorten a sentence and focus on its meaning. For example, there is Julius Caesar’s famous quip: “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

- Polysyndeton: The deliberate use of many conjunctions for special emphasis to highlight quantity or mass of detail or to create a flowing, continuous sentence pattern. For example, “We have ships and men and money and stores.”

- Chiasmus: A rhetorical or literary figure in which words, grammatical constructions, or concepts are repeated in reverse order. For example, “Never let a Fool Kiss You or a Kiss Fool You.”

- Litotes: A form of understatement that involves making an affirmative point by denying its opposite—i.e., an understatement that uses double negatives. For example, “Not too bad” for “very good.” Or: “He’s not the brightest” instead of saying “He’s dumb.”

- Synecdoche: A figure of speech in which a part is made to represent the whole or vice versa. For example, “All hands on deck,” where “hands” refers to people. Or: Referring to a car as “wheels.”

- Metonymy: A figure of speech in which a thing or concept is referred to by the name of something closely associated with that thing or concept. For example, “The pen is mightier than the sword,” where “pen” represents peaceful writing and “sword” represents military action. Or: Using “the crown” to refer to royal authority or monarchy.

- Apostrophe: A figure of speech in which the poet addresses an absent person, an abstract idea, or a thing. For instance, “O Death, where is thy sting?”

- Paradox: A statement that appears to be self-contradictory or silly but may include a latent truth. For example, “Fair is foul, and foul is fair.”

- Zeugma: A figure of speech in which a word applies to multiple parts of the sentence. For example, “He opened his mind and his wallet at the movies.”

- Anachronism: Placing a person, thing, event, or phrase in the wrong historical or chronological time. For example, depicting a Roman soldier using a smartphone.

- Anthropomorphism: Attributing human characteristics to a god, animal, or object. Unlike personification, which is metaphorical, anthropomorphism is more literal.

- Inversion: Changing the natural flow of language or inverting the word order to make an emphatic point. Yoda does this a lot in Star Wars: “Consume you, it will.”

Literary Devices Examples

Here are more examples of some literary devices to show how they can be used:

- Metaphor:

- “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” (William Shakespeare, “As You Like It”)

- This metaphor compares the world to a stage and people to actors, suggesting that life is like a play with various roles and acts.

- “He is a lion among men.”

- Simile:

- “Life is like a box of chocolates; you never know what you’re gonna get.” (Forrest Gump, 1994)

- This simile compares life to a box of chocolates to suggest its unpredictability.

- “Her smile was as warm as the sun on a midsummer day.”

- Personification:

- “The kites danced in the wind.”

- This gives the kites human qualities, suggesting they are dancing.

- “The ship ascended the giant wave with monarchical presence, smiling gently and wholly composed even in the face of the enormous tempest before it.

- Hyperbole:

- “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse.” Or: “I could eat a million burgers tonight.”

- This is an exaggerated statement to emphasize extreme hunger.

- Alliteration:

- “Billy bounced the basketball against the barn door.”

- The repetition of the ‘b’ sound creates a sound effect like that which is depicted.

- “She sells sea shells down by the sea shore. “

- Onomatopoeia:

- “The clock tick-tocked in the background.”

- The ‘ck’ imitates the sound a clock makes.

- Irony:

- Verbal irony: Saying “Great weather!” during a storm.

- Situational irony: A fire station burns down. A pilot has a fear of heights.

- Dramatic irony: In “Romeo and Juliet,” the audience knows Juliet is alive when Romeo believes she is dead. In Oedipus Rex, the audience knows the identity of Oedipus before he does.

- Symbolism:

- In “The Great Gatsby,” the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock symbolizes Gatsby’s hopes and dreams for the future.

- Foreshadowing:

- In “The Lord of the Flies,” the boys’ descent into savagery is foreshadowed by the gradual destruction of their clothes.

- “The buzzsaw bzzz-ed its way through the lumber.”

- In “Macbeth,” the witches’ prophecies foreshadow the rise and fall of Macbeth.

- Imagery:

- “The golden sun poured its warmth onto the fields, covered in a blanket of wildflowers.”

- This sentence creates a vivid picture of the scene, appealing to our senses of sight and touch.

- Allusion:

- “He was a real Romeo with the ladies.”

- This alludes to Shakespeare’s Romeo, a well-known romantic figure.

- “She had a Cinderella moment when the entire room turned to look at her.”

- This alludes to the fairy tale character, suggesting a transformation into grace and beauty.

- Allegory:

- George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” is an allegory for the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Soviet Union, with farm animals representing different groups in Soviet society.

- In “The Chronicles of Narnia” by C.S. Lewis, the story serves as an allegory for Christian themes, with Aslan representing Christ.

Conclusion

In conclusion, literary devices act as the muscles and sinews that help bring communication to life. They can be found in almost all forms of writing save technical: thus, from the poetic works of Wordsworth to the philosophical insights of Emerson and the whimsical reflections of Chesterton, literary devices can be formed. They transform ordinary language into extraordinary expression. They lift up prose to the skies and give it depth like the seas.

Literary devices also help to establish a deeper connection between the text and the reader. They engage the reader’s imagination and emotions, and invite them into a fuller contemplation of the themes and ideas presented. One can find in them the rhythms of alliteration and the beauty of allegory, the fascinating symbols and meaningful similes; with them, one experiences the text rather than just reads it.

For this reason, literary devices are the tools through which writers bring their thoughts and stories and essays and speeches into forms that captivate. They are the chisels and paint brushes and colors that artists use to make their writing superb. Learning to use literary devices wisely is one of the greatest achievements a writer can do.

Key Points to Remember

- Literary devices enhance expressiveness in writing.

- Literary devices help convey complex ideas in an understandable way.

- They add creativity and artistic flourishes to the text.

- Literary devices encourage readers to engage more deeply with the text.

- Literary devices should be used sparingly, appropriately and purposefully—otherwise you risk making your writing seem superfluous.

- Literary devices include metaphors, similes, personification, and hyperbole, which enhance descriptive language.

- Metaphors create direct comparisons without using “like” or “as.”

- Similes make comparisons using “like” or “as.”

- Personification attributes human qualities to non-human entities and can make abstract concepts relatable.

- Hyperbole involves exaggeration for emphasis.

- Irony presents contradictions between expectations and reality. Irony and satire are effective in critiquing social issues from a moral point of view assumed by the reader and writer alike.

- Symbolism uses symbols to represent ideas or qualities and allows for deeper layers of meaning in narratives.

- Imagery creates vivid sensory experiences and aids in creating great mental pictures.

- Alliteration and assonance enhance the musicality of prose and poetry.